Mental Health in Post-Conflict Kurdistan

Globally, the prevalence of poor mental health and the likelihood of developing a condition among adults and children living in conflict affected areas, or in individuals exposed to war and/or armed conflicts, are reportedly as high as one in five; half of which are severe. In Iraq and Kurdistan, a region still recovering from repeated and protracted conflict, lingering trauma, stress, and other mental health conditions continue to impact those who were exposed to intense fear and violence.

On September 2, 2024, Sherri Kraham Talabany, SEED’s Executive Director and President, joined the University of Sulaimani’s symposium, titled ‘The Significance and Function of Educational and Psychological Counseling in Society and the Labor Market’, which brought together experts to discuss the importance of mental health support in conflict-affected regions, particularly in the Kurdistan Region. Sherri spoke on a panel focusing on the role of psychological counseling in humanitarian aid.

Gaps in Mental Health Services During Crisis

“We found huge gaps in the mental health infrastructure during and after the ISIS crisis,” Sherri explained. “There were no regulations, no standards in the field of mental health, and a very limited understanding of the needs. The capacity to respond was also low, and resources were scarce.”

Despite the area’s long history of conflict, war, and displacement, in Iraq and Kurdistan, the government was not equipped to address the heightened mental health needs of its population. With the support of international donor funding, international and local actors such as SEED, worked with the government to fill these gaps. In addition to the mental health services provided to affected populations, tremendous resources were spent on building capacity, both in terms of training programs delivered to improve the skills of front-line workers, and also to strengthen the qualifications of mental health professional graduates through work improving and expanding university education in psychology and social work.

Throughout the last decade, SEED trained hundreds of government actors and NGO front line responders delivering mental health and psychosocial support and protection services on survivor-centered, trauma-informed care. SEED was also pleased to work with Koya University to strengthen its Clinical Psychology Program, integrating a one year trauma psychology course among other reforms, and with Salahaddin and Sulaimani Universities to strengthen their Social Work Programs. Across these three undergraduate programs, SEED and its partners worked to address the curricula to ensure that students received the most robust education that enabled them to address the needs of the population, supplementing theoretical knowledge with practical skills and understanding; through the introduction of interactive teaching methods fitting for such programs. During this same period, the University of Duhok with support of the state government of Baden-Wuerttemberg (Germany) through the University of Tübingen, introduced a masters program in Traumatology at the – then newly established, Institute for Psychotherapy and Psychotraumatology (IPP), giving mental health workers an opportunity to build much-needed clinical skills.

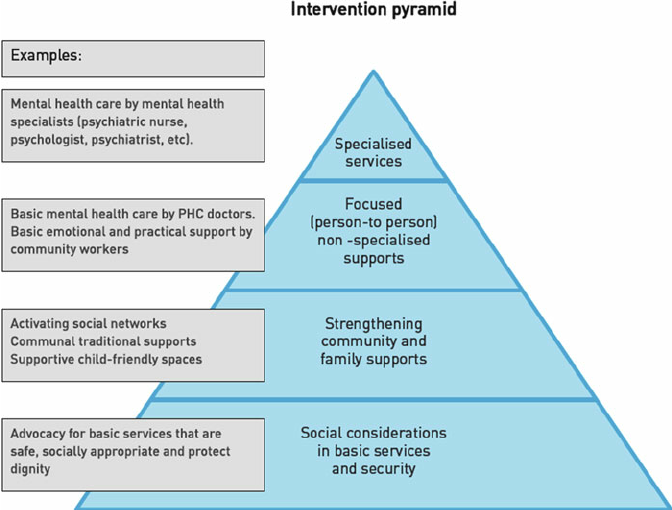

The Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) served as a key guide for this response during this phase of the humanitarian crisis. “The IASC Pyramid of Interventions helped us plan our response,” Sherri noted. “At the bottom of the pyramid, we have basic social and community-based services which can meet the majority of the population’s needs, and increasingly specialized services, with clinical services like psychological and psychiatric services at the top. The pyramid helps to ensure everyone gets the right level of care as per their specific needs.”

The IASC Pyramid of Interventions, ResearchGate, 2013.

During these years, SEED provided long-term, psychological services to individuals and families, delivered by skilled and highly-trained psychologists. SEED also worked to deliver MHPSS services at a community level through structured and unstructured group sessions to provide emotional support, build resilience, and strengthen support networks.

Through the establishment and strengthening of psychology and social work programs in universities, the opening of dedicated mental health facilities by the KRG such as the Survivor Center in Duhok, established by the Directorate of Health, and creation of private institutions, such as the Institute of Psychotherapy and Psychotraumatology (IPP), the KRG, civil society, NGOs and other key stakeholders worked to improve access to critical services, for the most part, supported by international donors.

Developing Mental Health Standards in Kurdistan

Despite the remaining high needs of the population, and expanding services, the regulation and oversight of mental health services to affected populations and the host community, was severely lacking. This led to differing standards at a minimum and, at times, services being delivered by those who were not qualified or supervised. The MHPSS Working Groups, created under the UN-led cluster system, which coordinated the mental health response to affected populations from 2014 – 2022, aimed to supplement local systems with international standards.

To address these systemic deficits, in 2018, SEED, as the co-lead of the Duhok MHPSS Working Group, developed a MHPSS Standard of Care (SOC) Model, which aimed to improve mental health services in Kurdistan and address the gaps left by the lack of standards and regulating body. This model was created to ensure greater clarity about standards and services, ensure higher quality services, and strengthen accountability in mental health service delivery, and serve as the basis for how services are delivered across the region during the crisis period and beyond.

In developing the SOC, SEED drew from the IASC guidelines and other international standards, and tailored the content for the local context in Kurdistan. SEED consulted widely on the model, integrating feedback from technical experts globally and in Kurdistan, as well as from the KRG, UN agencies, NGOs, and MHPSS working groups. In 2019, the SOC was adopted as a resource and guide by the MHPSS Working Groups.

Lessons for Post-Crisis Mental Health Care

Reflecting on the current situation, despite the almost six years since the end of the ISIS conflict, and two years since the UN dismantled the humanitarian cluster system, significant gaps remain both in terms of systems and available services. While there is increased attention and resources for mental health and mental health services have expanded across the region, there remains no government-led standard or system for ensuring the delivery of quality mental health services in Kurdistan. While the crisis has passed, humanitarian needs continue with large groups of displaced individuals remaining in Kurdistan. Moreover, the host community has high and unmet needs, both resulting from the long history of conflict, high levels of violence within the home, and tremendous destabilizing factors related to the economy and regional instability and security issues.

One of the barriers to people accessing help is stigma. Mental health is still taboo in Iraq and Kurdistan. Many people blame those with mental health issues, judge them, and fail to support them and there is low awareness of symptoms. All of this prevents people from seeking help.

As Kurdistan transitions beyond emergency response, the KRG can apply some lessons learned during the crisis with the IASC layers of support that can serve as the foundation for developing mental health systems now, ensuring that people have access to social services, community-based support, and specialized services. It is also critical to raise awareness and engage the community in supporting loved ones to get the help they need.

Sherri Kraham Talabany, President and Co-Founder of SEED at the University of Sulaimani’s Symposium on Mental Health. September 02, 2024.

A Collaborative Approach to Mental Health

Addressing mental health is multi-layered and we need the government, communities, and service providers all working together to make long-term improvements. Given the shortage of mental health professionals in Kurdistan, community based actors can expand the services available, especially in the lower tiers, while specialists focus on more complex cases.

While the crisis is abated for now, a strong mental health system is needed to support everything else—healthy families, strong communities, and economic development. Changing attitudes and building systems for mental health will take time, but it’s critical for a healthy and strong Kurdistan.